The Tour That Almost Killed George Harrison

via Music Box USA / youtube

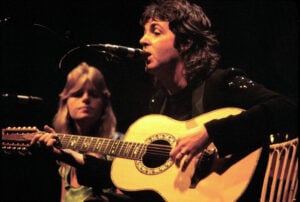

When George Harrison walked away from The Beatles, it felt like a giant weight had been lifted. For the first time, he was free to explore his own creative voice—and he wasted no time doing just that. All Things Must Pass revealed a songwriter bursting with ideas, finally stepping out from the shadow of Lennon and McCartney. Then came the Concert for Bangladesh, which made history not just musically, but politically and spiritually. With Living in the Material World, he dove deeper into introspection, blending melody with meaning, as if he had found his place and peace.

But peace can be fragile. By the mid-1970s, George’s life was unraveling. His marriage to Pattie Boyd was crumbling. He was exhausted, juggling a record label, a new album, and the planning of an ambitious North American tour. “My next move will be Madison Square Garden—after that, I’ll probably just collapse,” he quipped. What started as a dream tour quickly became a nightmare. His voice gave out, critics pounced, and audiences were left confused by the mix of Indian music and rewritten Beatles songs. It was a grueling experience—one that nearly broke him.

Building a New World

By 1973, George Harrison was riding a creative high. Surrounded by musicians, friends, and spiritual mentors, he seemed ready to shape his own artistic universe. Living in the Material World was released that year, featuring the hit single “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth),” which became his second U.S. number one. Another track, “Sue Me, Sue You Blues,” cheekily addressed Paul McCartney’s legal push to dissolve The Beatles. The album stayed atop the U.S. charts for five weeks. That same year, George launched Dark Horse Records, a label that reflected his evolving artistic and spiritual vision.

Breaking Down Behind the Scenes

While George Harrison was making music and building a new career, his personal life was falling apart. His marriage to Pattie Boyd was ending, and things were becoming more chaotic by the day. When asked by a reporter whether he had written a musical response to Eric Clapton’s “Layla,” which was famously inspired by Pattie, George calmly replied:

“How do you mean a musical rebuttal? I mean that sounds nasty doesn’t it? I mean, I just like to sort that one out. I love Eric. Eric Clapton’s been a close friend for years and I’m very happy about it. I’m very friendly with him…because he’s great. I’d rather she was with him than some dope. There’s nothing to say really.”

Despite his composed words, life behind closed doors was unraveling. Pattie Boyd described it candidly:

“Afterward everyone would sit down and smoke dope. From time to time there might be some cocaine which crept into our repertoire. George developed an interesting and extreme relationship with it. He was either using it every day or not at all for months at a stretch. Then he would be spiritual and clean and would meditate for hour after hour with no chance of normality. During these periods, he was totally withdrawn and I felt alone and isolated. Then, as if the pleasures were too hard to resist, he would stop meditating, snort coke, have fun, flirting and partying. Although it was more companionable, there was no normality in that either. George used coke excessively and I think it changed him. Cocaine was different, and I think it froze George’s emotions and hardened his heart.”

Longtime friend Klaus Voormann added:

“George stepped back and what I mean by step back to me means that he got very heavily into drugs and things which I don’t know the reason why that happened.”

George himself admitted:

“Yeah well after I split up from Patty I went on a bit of a bender to make up for all the years I’d been married. If you listen to ‘Simply Shady’ under Dark Horse, it’s all in there. My whole life at that time was a bit like Mrs. Dale’s Diary.”

The Tour Begins, But George Is Already Burning Out

By late 1974, George Harrison was running on fumes. Consumed by anxiety, exhaustion, and a need for validation, he was juggling too much: finishing his Dark Horse album, promoting new artists under his own label, and planning his first solo tour. And he was doing it all at the same time. When asked, “Is there a paradox between being spiritual and being entrepreneur with a band?” George admitted:

“Uh, it is difficult, you know it’s good practice in a way because it’s to be like they say be in the world but not of the world… I mean, that’s you know a famous saying. Go to the Himalayas—I miss it completely—and yet you can be stuck in the middle of New York and be very spiritual. It brings out a certain thing in myself… then somehow you know you have to look within yourself, otherwise you go crackers.”

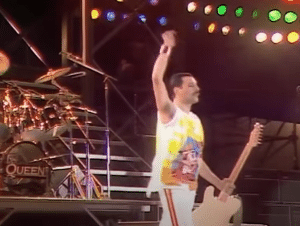

His 1974 Dark Horse Tour marked the first North American tour by any former Beatle since 1966. The hype was intense. But George made it clear this wouldn’t be a Beatles revival. At a press conference, he even claimed, “The Beatles weren’t that good compared to the musicians I’ve worked with afterwards,” and shut down any talk of reuniting with Paul McCartney. His setlist included only four Beatles songs: “Something,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” “For You Blue,” and “In My Life.”

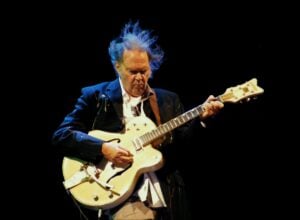

The tour featured a fusion of sounds—soul, jazz, and Indian classical music—with Ravi Shankar leading one half of the band. But rehearsals were rushed. The album was completed in a hurry. George was suffering from severe laryngitis, and he hadn’t sung live in years.

“Recommended by Eric Clapton, Barbara Streisand and many other top-notch singers and entertainers—and your throats will never bother you again—you just want to have a throat.”

His weak voice and spiritual lectures clashed with fan expectations. “Yeah it probably his voice probably was very weak or you know and beat up,” said drummer Jim Keltner. “But that did not deter George… they just loved hearing those songs and him trying to deliver them best he could.”

A Stage Full of Pressure, Not Praise

By the time George Harrison reached Los Angeles for the first of three shows at The Forum, the cracks were showing—both in his voice and in his spirit. After a weak 8-second reaction to his new song “Maya Love,” George told the crowd, “I don’t know how it feels down there but from up here you seem pretty dead.” His frustration only grew when a fan yelled out “Bangladesh.” With his voice breaking, he snapped:

“I have to rewrite the song but don’t just shout Bangladesh—give them something to help. You can chant Krishna, Krishna, Krishna and maybe you’ll feel better, but if you just shout Bangladesh, Bangladesh, Bangladesh, it’s not going to help anybody.”

Fans had hoped for a nostalgic, feel-good show packed with Beatles hits. But George had different plans. He blended rock with Indian classical music, spiritual messages, and reworked Beatles lyrics. He sang, “If there’s something in the way, remove it,” turned “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” into “While My Guitar Tries to Smile,” and most controversially, “In My Life, I Love God More.”

Many fans were puzzled. Half the show was devoted to Indian classical music led by Ravi Shankar—rich in culture, but hard to connect with for Western audiences. His performance felt scattered and under-rehearsed, filled with long talks and weak vocals. The New Yorker called it “an unfortunate experience.”

Even commercially, momentum faded fast. The Dark Horse album hit number five in the U.S., but didn’t chart in the U.K. The title single reached only number 15 on Billboard. George was overwhelmed—by expectations, personal turmoil, addiction, and the growing sense that everything was unraveling. At the tour’s end, after a group singalong of “My Sweet Lord,” George said, “See you in 8 years,” and ran off stage.

Olivia, Redemption, and the End of the Road

In a Rolling Stone interview, George Harrison was asked, “Were you going down fast?” His answer was honest and unfiltered:

“Well I wasn’t ready to join Alcoholics Anonymous or anything. I don’t think I was that far gone but I could put back a bottle of brandy occasionally plus all the other naughty things that fly around. I just went on a binge, went on the road, all that sort of thing until it got to a point where I had no voice and almost nobody at times. Then I met Olivia, and it all worked out fine.”

Amid the whirlwind of his collapsing tour and mounting stress, George opened the offices of Dark Horse Records on Labria Avenue in Los Angeles. That’s where he met Olivia Arias, a young records worker. What began as a professional connection turned into something much deeper. They bonded over shared interests—music, meditation, Indian culture, and a longing for peace.

By the time the Dark Horse tour began in 1974, Olivia had joined the label team and become George’s partner. She was with him through every show as he struggled on stage. In her, George found the clarity to start over. When the tour ended in December, exhausted in every way, he walked away from performing and said:

“I’m never doing this again. If you see me on tour again, I’ll be disguised as someone else.”

Not the Return Fans Expected—But Something Deeper

Let’s not forget—this was the very first U.S. tour by a former Beatle. John never did it. Paul and Ringo came later. The anticipation was massive. But what was meant to be a glorious return turned into something far more complicated. For many, the Dark Horse Tour seemed like a disaster. But in truth, it was an act of defiance. George wasn’t trying to live up to anyone’s expectations—he was choosing to explore, to stumble, and to be unapologetically himself.

He no longer wanted to please the crowd. He wanted to grow. Even if the world wasn’t ready to see him that way, he had the courage to reveal his darkest, rawest self. And in doing that, George may have been a pioneer. Not many artists dare to show such vulnerability on such a big stage.

As George once said with his signature wit:

“Anyway. It’s nice working with you. And it’s nice to know that the best sales force in the world is selling Darkhorse Records. Don’t drink too much, and I’ll see you. Thanks a lot again. Keep up the good work and in the meantime, I’m just going to write my new album which goes like this, ‘You can go your own way…’ Oh no, that’s not it.”