53 Years Ago: The Mystery of Jimi Hendrix’s Death — Murder, Mafia, and Unanswered Questions

via Alabaster Jones / YouTube

In February 1973, at Mike Jeffery’s London apartment, James ‘Tappy’ Wright, a longtime associate, and friend, gathered with Mike. They discussed the film “Jimi Plays Berkeley,” which featured Jimi Hendrix’s remarkable May 1970 concert. Mike had the idea to tour the film with support from live acts, a successful venture in the UK and Europe. As they planned to take the concept to the United States, they reminisced about Jimi and his final days.

During their conversation, Mike became agitated and pale, revealing something shocking.

He confessed:

“I had to do it. Jimi was worth much more to me dead than alive. That son of a bitch was going to leave me. If I lost him, I’d lose everything.”

Tappy inquired, and Mike cryptically explained that he had no alternative due to financial struggles and threats to his life. He mentioned involving unidentified acquaintances from the North, likening the situation to a scene from the film “Get Carter.”

View this post on Instagram

Barely a month later, in March 1973, Mike Jeffery met a tragic end while flying back from Majorca.

His Iberian Airways DC-9 flight was involved in a mid-air collision over France, resulting in no survivors. Mike, who had a fear of flying, used to make multiple flight reservations and choose his flight at the last minute to avoid any ill fate. However, on this fateful day, his luck ran out, and the full truth behind his shocking confession died with him.

Tappy Wright admitted that he never sought corroborative evidence for Mike’s story, fearing that those involved might consider him a threat if they believed Mike had disclosed everything. He confided in his close friend, Bob Levine, a part of Jimi’s management team in New York, who advised him to stay silent and disappear.

Tappy eventually moved back up north and became a club owner. In the early 80s, rock manager Rod Weinberg reformed The Animals, and Tappy was brought back into the business to help manage conflicts between Eric and Chas. Their discussions about the past eventually led to the idea for the book, which they began working on in 1999.

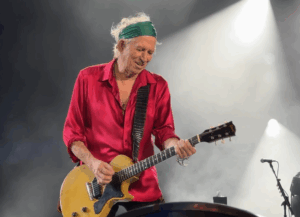

The motive behind Mike Jeffery’s alleged involvement in Jimi Hendrix’s death remains a mystery. Going back to September 1966, when The Animals had disbanded, Chas Chandler, the bassist, discovered Jimi Hendrix and tried to secure a deal for him even before bringing him to the UK. However, no one was interested initially. Chas struggled to make deals even after introducing Jimi to the London club scene, where he left a profound impact on musicians like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Pete Townshend.

Realizing the need for a business partner, Chas turned to Mike Jeffery, despite mistrust from The Animals, who believed Mike was involved in offshore tax schemes to steal their money. John Hillman, the lawyer overseeing the offshore company Yameta in the Bahamas, asserted that “The Animals without Mike Jeffery were nothing.” Chas and Mike became business partners, with Mike’s connections and expertise now on their side.

View this post on Instagram

Mike Jeffery, born in South London in March 1933 to postal worker parents, had an unremarkable school career but was known for his athleticism.

Mike Jeffery had a mysterious military career, claiming involvement in various covert operations, including the Suez Crisis and counter-espionage work. His intelligence and resourcefulness were evident when he made money selling old newspapers to British soldiers in Egypt during his service.

In the music industry, Jeffery managed Jimi Hendrix and played a pivotal role in Jimi’s career. He signed Jimi to a management contract that excluded other band members, considering them as employees. He secured lucrative deals with record labels, particularly Warner Brothers, with a substantial promotion budget and exclusive rights to Jimi’s master recordings.

Jeffery’s unique arrangement with Warner Brothers gave his company, Yameta, perpetual ownership of Jimi’s masters, a rare feat even among iconic artists like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. This highlighted his shrewd business acumen and ambition to maximize Jimi’s success.

View this post on Instagram

With the backing of a major US label, the Jimi Hendrix Rock Machine embarked on a lucrative journey.

They prioritized the US, extending tours, increasing concert fees, and embracing self-promotion. Mike Jeffery’s approach streamlined operations, reducing the number of promoters, and capitalizing on merchandising for added income.

“By mid-1968, cracks were appearing in the organization,” with Jimi resenting Chas’ creative influence and Chas disapproving of drugs and growing entourages. Jimi’s dissatisfaction included constant touring, the need for theatrical antics, and the monotony of repetitive songs.

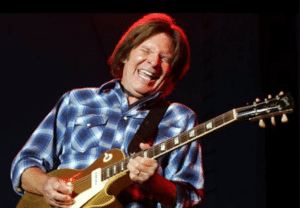

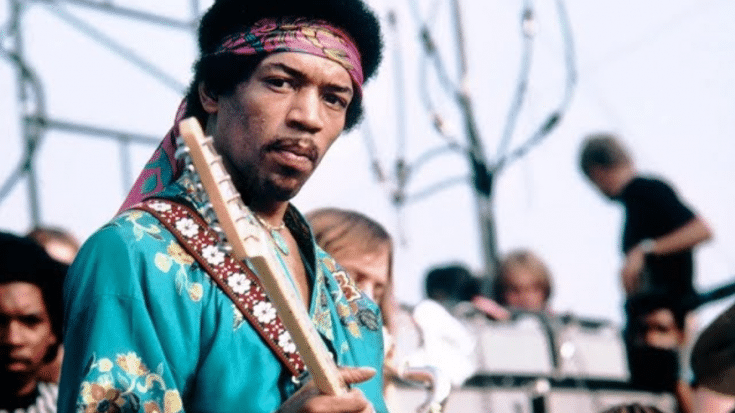

“In the summer of 1969, matters came to a head,” as the band’s performances became inconsistent due to Jimi’s mood swings. Noel Redding departed, and Jimi explored “Sky Church Music,” assembling new musicians. Their Woodstock performance before 30,000 people left Mike frustrated.

“Despite all the success, the cash was running out.” While recording deals were lucrative, extracting funds from record companies proved arduous, leading to a reliance on touring. Jimi’s hiatus ended with the Cry Of Love tour in April 1970.

As the income dwindled, expenses spiraled out of control, leading to financial woes for Jimi Hendrix and Mike Jeffery.

Jimi was extravagant with studio costs, especially during the making of “Electric Ladyland,” which cost $60,000. The band indulged in luxuries like limousines, hotels, and covering expenses for hangers-on. Jimi’s love for fast cars and impulsive guitar purchases added to the financial strain.

Mike Jeffery, too, was no stranger to spending. He aimed to be accepted among American rock management elites and adopted a more hippy appearance, experimenting with drugs. In 1969, he purchased a pricey house in upstate New York and rented one for Jimi.

The establishment of Electric Lady Studios became a financial abyss. Originally conceived as a club, it evolved into a state-of-the-art studio in a problematic location within Mafia territory. Building permits and flooding issues plagued the project, and Jeffery’s impulsive spending worsened cash flow problems. Despite securing a hefty loan from Warner Brothers, the budget ballooned far beyond the initial $500,000.

Desperate for funds, Jeffery took the perilous step of borrowing money from the Mob, facilitated by Bob Levine. This decision came with serious consequences, as gangsters demanded payment, reinforcing Jeffery’s respect after a death threat.

Furthermore, Jeffery faced scrutiny from the American Inland Revenue Service (IRS) due to Jimi’s inability to benefit from the Yameta tax haven as a US citizen. To bypass IRS restrictions, Jeffery’s assistants, Trixie Sullivan and Kathy Eberth, smuggled cash into the US. The IRS even threatened to seize Electric Lady Studios, keeping Jeffery in constant need of cash to navigate his precarious financial situation.

Concert promoter Ron Terry noted that Jeffery lacked forward planning, reacting to financial crises as they arose, placing immense pressure on Jimi and their working relationship.

View this post on Instagram

Mike Jeffery’s growing concerns extended beyond his deteriorating relationship with Jimi Hendrix; he also feared threats to his position and income in the music industry, a realm rife with suspicion and paranoia.

Mike’s Cold War involvement seemed to have heightened his sense of paranoia. He was wary of individuals who held closer ties to Jimi than he did, often attempting to manipulate situations to maintain control.

Initially, Mike applied this divide-and-rule strategy to figures like Chas Chandler and members of the Record Plant staff, such as producer Eddie Kramer and engineer Gary Kellgren. However, by 1969, Mike’s paranoia intensified, leading him to bug Bob Levine’s office as he felt increasingly distant from Jimi and his inner circle. Michael Goldstein, the band’s PR agent in the United States, noted that Mike “would stop at nothing to ensure the success of his artists but couldn’t relate to them personally.”

Mike’s frustration grew as Jimi refused to tour, which he attributed partly to Jimi’s revived collaboration with drummer Buddy Miles. Furthermore, Jimi began working with a new producer, Alan Douglas, whom he met through New York groupie Devon Wilson. Despite Jimi’s fondness for Douglas’s more bohemian, laid-back approach, the recording sessions proved unproductive. Alan Douglas decided to part ways with Jimi in December 1969, unable to match Mike Jeffery’s influence.

Despite these challenges, Jimi pressed ahead with plans for a new band featuring Buddy Miles and bassist Billy Cox, performing two dates at Fillmore East with the Band Of Gypsys before Mike intervened. Mike not only fired Buddy but insisted that Jimi reassemble the Experience, with Noel Redding on standby. Ultimately, the Cry Of Love tour began with Billy Cox on bass and Mitch Mitchell.

While the US tour generated income, Mike faced mounting debts. A critical element in this story revolved around whether Mike had taken out an insurance policy on Jimi’s life. Warner Brothers had initiated such a policy when they renegotiated with Jimi in 1968, following a standard practice since Otis Redding’s death in 1967. Mike had prepared a similar policy, which Jimi was presented with while in Hawaii filming Rainbow Bridge. Bob Levine spotted it and reportedly warned Jimi not to sign it, a claim corroborated by others.

View this post on Instagram

Despite the appearance of Jimi Hendrix getting back on track in Mike Jeffery’s eyes, their relationship was deteriorating rapidly.

Jimi was infuriated by Mike’s interference in his creative decisions, particularly his involvement in forcing Buddy Miles out of the band. Mike, aware that his management contract with Jimi was set to expire on December 1, 1970, grew increasingly convinced that Jimi might leave him.

Jimi, though, had been working at Electric Lady Studio for about a month, and the last thing he wanted was more touring. However, he reluctantly signed contracts to tour Europe in the autumn of 1970. The performances were lackluster, with a disastrous show in Arhus, Denmark, where Jimi struggled due to the effects of unidentified pills he had taken earlier. Worse was to come in Germany on the Isle of Fehmarn, marked by terrible weather and clashes with Hell’s Angels, symbolizing the downward spiral of Jimi’s career.

Mike Jeffery was acutely aware that his time with Jimi was running out. He faced a mountain of debt, including obligations to the Mafia and the IRS. While Mike’s management contract with Jimi ended at the close of 1970, he still had significant investments in Jimi’s career. He owned half of Electric Lady Studio, had various considerations from Warner Brothers’ 1968 deal with Jimi, and retained rights to two films, “Jimi Plays Berkeley” and “Rainbow Bridge.”

Despite Jimi’s talk of finding a new manager, no suitable replacement had emerged. Alan Douglas was mentioned, but Jimi knew that he couldn’t match Mike’s effectiveness. It would require a major player willing to challenge Mike Jeffery. Mike may have believed that losing Jimi meant losing a share of the concert revenue, a critical source of income, fueling his paranoia over money and Jimi. It’s possible that Mike calculated that Jimi Hendrix could be more financially valuable to him dead than alive, but the question remained: Did he orchestrate Jimi’s demise?

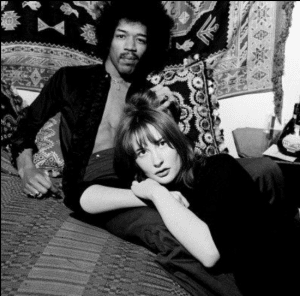

The crucial details surrounding the last hours of Jimi Hendrix’s life are illuminated through the testimony of Monika Dannemann, a German artist with whom Jimi had a brief encounter in early 1969 and reconnected with shortly before his death. Monika claimed that Jimi had kept in touch with her through private letters. In an interview conducted in 1989, Monika recounted her story, which she had shared with the coroner during Jimi’s inquest and with various journalists and writers over the years.

According to Monika’s account, Jimi was officially staying at the Cumberland Hotel near Marble Arch but was actually residing with her in the basement flat of the Samarkand Hotel, a 10-minute drive away. On the afternoon of September 17th, they visited a flat near Baker Street with some newly met acquaintances. They returned to the Samarkand around 8:30 pm and remained there until the early morning hours when Jimi asked to be driven to another flat near the Cumberland Hotel. His intention was to inform Devon Wilson, who had flown in with Alan Douglas and his wife, that he was engaged to be married.

Monika dropped Jimi off at the other flat, returned approximately 30 minutes later, and they went back to the Samarkand around 3 am. They had a conversation, and Monika even made Jimi a sandwich. They went to bed around 6 am. Monika took a sleeping pill and fell asleep about an hour later. When she woke up at 10 am, she found Jimi asleep but noticed that he had been sick, and her attempts to wake him were unsuccessful.

View this post on Instagram

The crucial details surrounding the last hours of Jimi Hendrix’s life are illuminated through the testimony of Monika Dannemann, a German artist with whom Jimi had a brief encounter in early 1969 and reconnected with shortly before his death.

Monika claimed that Jimi had kept in touch with her through private letters. In an interview conducted in 1989, Monika recounted her story, which she had shared with the coroner during Jimi’s inquest and with various journalists and writers over the years.

According to Monika’s account, Jimi was officially staying at the Cumberland Hotel near Marble Arch but was actually residing with her in the basement flat of the Samarkand Hotel, a 10-minute drive away. On the afternoon of September 17th, they visited a flat near Baker Street with some newly met acquaintances. They returned to the Samarkand around 8:30 pm and remained there until the early morning hours when Jimi asked to be driven to another flat near the Cumberland Hotel. His intention was to inform Devon Wilson, who had flown in with Alan Douglas and his wife, that he was engaged to be married.

Monika dropped Jimi off at the other flat, returned approximately 30 minutes later, and they went back to the Samarkand around 3 am. They had a conversation, and Monika even made Jimi a sandwich. They went to bed around 6 am. Monika took a sleeping pill and fell asleep about an hour later. When she woke up at 10 am, she found Jimi asleep but noticed that he had been sick, and her attempts to wake him were unsuccessful.

Monika Dannemann’s account of the events leading to Jimi Hendrix’s death involves her discovering Jimi’s condition and calling an ambulance.

She claimed the ambulance arrived calmly and that the paramedics kept Jimi upright during transport to St Mary Abbott’s Hospital. Monika blamed the medical staff, particularly the ambulance drivers, for Jimi’s death.

However, doubts arose about Monika’s story when investigations were conducted. The hospital’s admissions register for August 18, 1970, did not contain any record of Jimi’s admission, and a hospital porter, Walter Price, stated that Jimi had never been admitted but had been taken directly to the morgue.

“Jimi was never admitted,” Walter Price told Monika. “He was taken straight to the morgue.”

Inconsistencies in Monika’s statements and actions further fueled skepticism about her account. These findings led to a clearer understanding of what transpired and cast doubt on Monika’s narrative. In response, Monika threatened legal action against those who questioned her credibility.

As Tappy and others close to Jimi noted, he often fell in love passionately and made promises of marriage to women, charming his way into their affections. Monika believed that Jimi was genuinely committed to marrying her and starting a life together in England, but the reality might have been different.

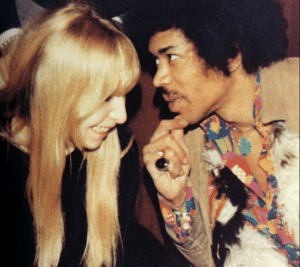

Kathy Etchingham, the woman Jimi Hendrix genuinely cared about without ulterior motives, played a significant role in uncovering the circumstances surrounding Jimi’s death.

Kathy, aided by Mitch Mitchell’s wife Dee, took on the task of investigating Jimi’s passing in the early 1990s.

Surprisingly, none of the ambulance drivers, police who responded to the 999 call, or hospital doctors who attempted to revive Jimi were ever called to provide evidence during the initial investigation. Coroner Gavin Thurston seemed eager to conclude the case swiftly, issuing an open verdict that cited inhalation of vomit due to barbiturate intoxication as the cause of death, with no indication of foul play or suicide.

Kathy and Dee diligently tracked down these individuals and gathered substantial new evidence, prompting the Attorney General to order a police investigation. However, some individuals who had spoken privately to Kathy were reluctant to cooperate with the police or altered their stories due to fear of publicity. Consequently, the inquest was not reopened, but the testimonies they provided remain on record.

The revised account of events indicates that while Monika and Jimi did visit the flat of strangers in the afternoon, Jimi stayed longer than Monika desired, enjoying the company of young women present. Later, they went to a party hosted by a businessman linked to Track Records, Peter Cameron. Attendees included Devon Wilson, Alan Douglas, and his wife Stella. Monika returned to collect Jimi but was met with resistance. Eric Burdon inquired why she hadn’t called an ambulance, to which Monika expressed fear due to drugs in the room. Eric’s roadie, Terry Slater, and Monika cleared the flat, burying the drugs in adjacent gardens. The ambulance drivers found Jimi dead and alone in the room, attempting resuscitation in accordance with protocol. The hospital doctors also tried to revive him but realized it was futile, as Jimi had been dead for hours.

View this post on Instagram

Monika Dannemann’s accounts of the events leading to Jimi Hendrix’s death exhibited significant inconsistencies over time.

Critical details, such as bedtime, her movements, and the sequence of events, varied in each retelling. It was revealed that Jimi had ingested nine of Monika’s German sleeping tablets, equivalent to 18 times the recommended dose, which ultimately caused his death. Her motivations for not immediately calling for an ambulance raised questions. She may have blamed herself for leaving the pills accessible or felt guilty about Jimi taking the excessive dose, possibly to escape her constant nagging. Another possibility was that, as a 22-year-old foreigner from a conservative background, she panicked upon discovering Jimi dead in a room filled with drugs and fled, leading to her inconsistent stories.

Monika’s repeated admission of not promptly calling for an ambulance contributed to the belief among fans and musicians that her delay was responsible for Jimi’s death.

During this period, Mike Jeffery’s whereabouts were a subject of scrutiny. He had been in London on September 13th to visit Danny Halpern at Track Records, primarily to discuss an impending court case regarding claims that Jimi had signed a deal with PPX Records before partnering with Chas and Mike. However, it was contested whether Mike stayed in London. His assistant, Trixie Sullivan, and Jim Marron claimed that Mike was in Majorca when news of Jimi’s death broke. In contrast, Bob Levine asserted that Mike only contacted the New York office a week after Jimi’s death, pretending he had just learned of it. Levine argued that he knew Mike was lying because he had spoken to people who saw Mike at a party hosted by Track Records in London the night before Jimi’s death. These people allegedly included Devon Wilson, Alan Douglas, and Stella Douglas, who had also been present at the flat of Peter Cameron, an individual connected to Track Records, where Jimi had been seen later that evening. This raised questions about whether Mike’s arrival and departure from the party were linked to Jimi’s presence and the events of that fateful night.

Despite extensive investigation by Kathy Etchingham and Dee Mitchell, two significant and puzzling aspects of Jimi Hendrix’s death remained unexplained.

Firstly, Jimi was found fully clothed and on top of the bed, contrary to every version of Monika Dannemann’s story, which indicated that they had gone to bed together, implying undressing and pulling back the covers.

Secondly, both the ambulance drivers and the attending doctor at the hospital noted that Jimi was in a dire condition. Dr. John Bannister, the surgical registrar on duty, remembered a significant amount of alcohol in Jimi’s larynx and pharynx. He vividly recalled the large amounts of red wine that had seeped from Jimi’s stomach and lungs. However, the toxicology report revealed an alcohol blood level equivalent to about four pints of beer, and Jimi was known to have a low tolerance for alcohol. There was no indication from Monika’s testimony or any other source that Jimi had consumed a substantial amount of wine that night, nor were there empty wine bottles in the room. This raised questions about where the alcohol had come from and how it had ended up in Jimi’s system.

The open verdict issued by the coroner brought relief to Warner Brothers and Mike Jeffery. If the verdict had suggested suicide, foul play, or reckless behavior contributing to Jimi’s death, insurance companies might have refused to pay out. An insurance investigator who had looked into Jimi’s death before confirmed that he had been searching for ways to avoid payment but did not disclose the contents of his files.

Eric Burdon, under the influence of drugs, went on British television and suggested that Jimi had died by suicide based on a poem Jimi had written before his death. This led to a stern warning from Warner Brothers. For Mike Jeffery, if he believed he was about to lose Jimi, as Noel Redding later pointed out, Jimi’s death was rather convenient for Mike’s financial well-being. According to Tappy, Mike managed to clear all his debts and offered Jimi’s father, Al, nearly $250,000 for Jimi’s half-share in Electric Lady Studios.

In the aftermath of Jimi Hendrix’s death, there were rumors circulating that Mike Jeffery might have been involved.

Monika Dannemann, who had been close to Jimi, visited Mike at Electric Lady studio in New York in February 1971. They discussed the possibility of Mike becoming her manager to promote her artwork. Monika resisted his offers and eventually left for Seattle. However, the reasons for seeking out Mike Jeffery in the first place remained unclear.

The premature death of Jimi Hendrix at the age of 27 was followed by the untimely deaths of other key figures in his life. Devon Wilson, who struggled with heroin addiction, died in mysterious circumstances, falling from the Chelsea Hotel in February 1971. Mike Jeffery passed away at the age of 39 in 1973. For Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, life after the Jimi Hendrix Experience was challenging, marked by heavy drinking and obscurity. Noel passed away at 57 in May 2003, and Mitch followed in 2009 at the age of 61. Chas Chandler, Jimi’s former manager, also died young, succumbing to a heart attack at 57 in July 1996. Hendrix historian Tony Brown, who extensively documented the events leading up to Jimi’s death, also died in his fifties.

As Monika Dannemann’s story began to crumble under the weight of new evidence, she faced a court order obtained by Kathy Etchingham that prevented her from spreading further falsehoods about Kathy and her investigation. Monika violated the order and was found guilty of contempt of court in April 1966. Just two days later, she died by suicide, her body discovered in a fume-filled Mercedes at her home in Seaford.

The circumstances surrounding Jimi Hendrix’s death between 4 am and 8 am on September 18, 1970, remain shrouded in mystery. While the inquest was not reopened, the case remains open, as there is no statute of limitations on murder.

Sources:

“Rock Roadie” (2009) by James ‘Tappy’ Wright and Rod Weinberg