How Ozzy Osbourne Sent a Belfast Teen to Rock in Rio

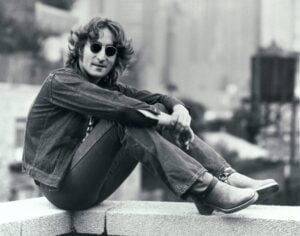

via Ozzy Osbourne / YouTube

At 6 p.m. on Thursday, November 1, 1984, the nightly news flickered on a ten-inch black-and-white TV in a cramped Belfast kitchen. Another grim update from Northern Ireland played across the screen. Meanwhile, fourteen-year-old music fanatic — four weeks shy of his fifteenth birthday — sat at the family’s worn pine table in full school uniform, devouring fish sticks and Kerrang! issue 80.

On page three, a photograph of Ozzy Osbourne unexpectedly joining Iron Maiden onstage caught his eye. But it was the sidebar beside it that made him freeze:

A major ten-day rock festival is to take place in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) between January 11–20 next year… Among the top names already confirmed are Queen, Rod Stewart, Def Leppard, George Benson, James Taylor, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Nina Hagen, the B-52’s, the Go-Gos, Al Jarreau, Ozzy Osbourne, and the Scorpions.

He muttered aloud, “Ozzy is playing a big festival in Rio.”

His father, eyes fixed on the television and sipping heavily sugared tea, turned just long enough to respond:

“Find out about it. I’ve always wanted to go to Brazil.”

It wasn’t a joke. His parents, far from wealthy, valued experiences over comforts. They had taken him abroad since he was an infant—Majorca under Franco, two holidays in Florida in the early ’80s, and Spain for the 1982 World Cup. Travel was part of their family identity, even if Brazil seemed impossibly distant.

A Fan Letter, a Phone Call, and an Unexpected Ally

His father’s shop sat next to a travel agency. Within days, the staff produced a flimsy four-page leaflet from a tour operator in London—uninspired photos, a list of festival dates, and a thirteen-night tour priced at £895 per person. A note warned, “The price does not include surcharges arising from unavoidable increases in costs due to Government action,” a hint at Latin America’s political volatility. With flights and spending money, the modern equivalent would top $15,000.

Still searching for clarity, his mother wrote to Ozzy Osbourne’s fan club, mentioning her son’s early membership number. The following Thursday, he returned from playing football to find his mother startlingly calm.

“Ozzy Osbourne’s secretary called,” she said.

It was technically Sharon Osbourne’s assistant, Lynn, who managed the fan club. Overworked and juggling constant phone calls, she could easily have ignored the letter—but instead she tracked down their number and phoned personally. His mother jotted down the details: Ozzy’s performance dates, the band’s hotel, and their arrival schedule.

“Lynn told me not to buy tickets to the concert,” she said. “If we make it to Rio, they’ll get us in for free. She gave me her number and said you should call her. She wants to speak to you herself.”

The boy went to bed stunned, spending hours staring at the ceiling. It was the kind of moment teenage fans fantasized about, yet he had never imagined something this surreal could happen to him.

Over November and December, he and Lynn spoke regularly. Despite being a twentysomething industry professional with constant interruptions from her second phone line, she treated him warmly, even sharing an embarrassing Rod Stewart anecdote “not even Ozzy and Sharon know.” Their conversations were unlikely but genuine—a teenage metal fan in Belfast and a young music-business insider navigating tour logistics.

The School That Said Yes—Reluctantly

Campbell College, his strict all-boys Northern Irish school, posed the biggest obstacle. The festival ran January 11–20, right in the middle of term. The idea of granting a student two weeks off for a rock festival bordered on absurd. This was a school where boys wore caps and shorts until age thirteen, stood whenever an adult entered the room, and queued in silence at the sweet shop run by the principal’s wife. Classes were held six days a week, including Saturdays.

Still, his mother wrote a carefully worded letter, and he delivered it to the headmaster’s Victorian study after rehearsing his plea dozens of times.

A week later, he returned home and saw an envelope on the floor beneath the telephone bench, its arrival announced by the postman’s signature force. He picked it up, traced the embossed crest, and opened it.

The headmaster’s letter called the request “highly irregular,” “unsatisfactory,” and warned about setting precedents. But after consulting with the boy’s housemaster, who described him as “pure gold,” the school relented.

The decisive line read:

“I acquiesce, under protest, and ask that it does not happen again.”

He didn’t actually know what “acquiesce” meant. He pulled out his battered pocket dictionary, flipped through the pages, and when he found the definition, adrenaline surged through him. He called his parents at work—he couldn’t wait to say the words out loud.

It was happening.

A Turning Point in Real Time

Looking back, this moment didn’t just mark approval for a once-in-a-lifetime trip. It signaled something bigger: the first time the world cracked open for him. A kid who had grown up in a city overshadowed by conflict suddenly found himself connected to a global music scene, speaking regularly with someone inside Ozzy Osbourne’s camp, and preparing to attend a landmark festival few fans his age could even dream about.

It was more than permission to miss school.

It was the first sign that passion could rewrite the rules adults insisted were fixed. That music could pull a Belfast teenager across an ocean. That sometimes—against logic, bureaucracy, and geography—a door opens, and the only thing left to do is step through it.

And for him, Rio wasn’t just a destination.

It was the start of everything.